The Charles Darwin Research Centre

The Charles Darwin Research Centre is a stop for pretty much everybody that visits the Galapagos. It was opened in 1964 and conducts research, monitoring, and conservation projects in conjunction with the National Park authorities. They have an exhibition area where you can learn about a lot of their projects (and also about the Galapagos islands in general), and you can also view some of the tortoises which are part of the breeding program which has been run since 1965.

The area is quite spread out, but easily walkable from town – and there are also a couple of beaches along the way – so it’s easy to spend a lot of time there. We went in the morning, but by the time we got to the exhibition centre area it was closed for lunch! So, of course we went back to town to have lunch, and then returned to the centre again in the afternoon! 🙂

The purpose of the breeding centre is to try and restore the wild galapagos tortoise population of the various islands. Galapagos tortoises are not a single species – from a scientific point of view, they are a ‘species complex’ – as the tortoises on each island have evolved totally separately from each other. In fact, on Isabela, which is the largest island – different tortoise species have actually evolved around different volcanoes on the same island.

The reason for this separation, is to do with the way that the Galapagos islands have been formed. There is a volcanic ‘plume‘ under the Galapagos, which occasionally erupts, sending magma up to the sea floor, and creating a new island. Because the Nasca tectonic plate that is above the plume is moving, then each time the plume erupts, the island is formed in a different place – because the earth’s surface has moved. The plate is moving eastwards, and so the first islands that were created are on the east side of the Galapagos, and the most recent islands are on the west side of the Galapagos.

The islands are reasonably close together, because of course the plate doesn’t move particularly fast! 🙂 It moves at around half a centimetre PER YEAR! But this is enough, given how often the eruptions have occured – the oldest islands are around 3.2 million years old, and the newest island – Fernandina – is ONLY around 50,000 years old. So, we could be due a new island sometime in the next 10,000 years or so! 🙂

When the Galapagos islands were formed there were of course no animals on them. Due to their location almost 1000km from the coast of South America, it was very hard for any animals to end up on these islands. However, some reptiles and very small mammals managed to end up on the islands – arriving accidentally on floating ‘rafts’ of reeds. Tortoises can survive for months without food and fresh water – allowing them to survive a 1000km floating voyage to the Galapagos.

So over 3 million years ago, some tortoises from South America ended up on the Galapagos, and then they basically had 3 million years to evolve into giant tortoises – and ended up COMPLETELY different from any tortoises on the mainland. They evolved to suit the conditions on the islands.The theory is that this process was started on the oldest islands, and when new islands were created, some tortoises from the existing islands ended up floating over to the newer islands and started a whole new evolutionary process.

Therefore the tortoises on each island evolved separately and adapted to that island – forming different species. There is disagreement as to whether some of the tortoises from the different islands are technically different ‘species’, or if they are ‘sub-species’ – but nonetheless, they are different!

The tortoises happily lived on the islands, undisturbed for around 3 million years….and then suddenly a few hundred years ago, people turned up on the islands…

This was a disaster for the tortoises. In the 1600s there were around 250,000 of them, but by the 1970s there were only around 3000 left. Between being eaten, having their habitat destroyed, and the introduction of invasive animals that ate their eggs, the tortoises didn’t have much chance.

There is slight disagreement about the actual number of species of Galapagos tortoise, but in theory there are 10 species still around, 1 species that became extinct in 2012, and 2 other extinct species.

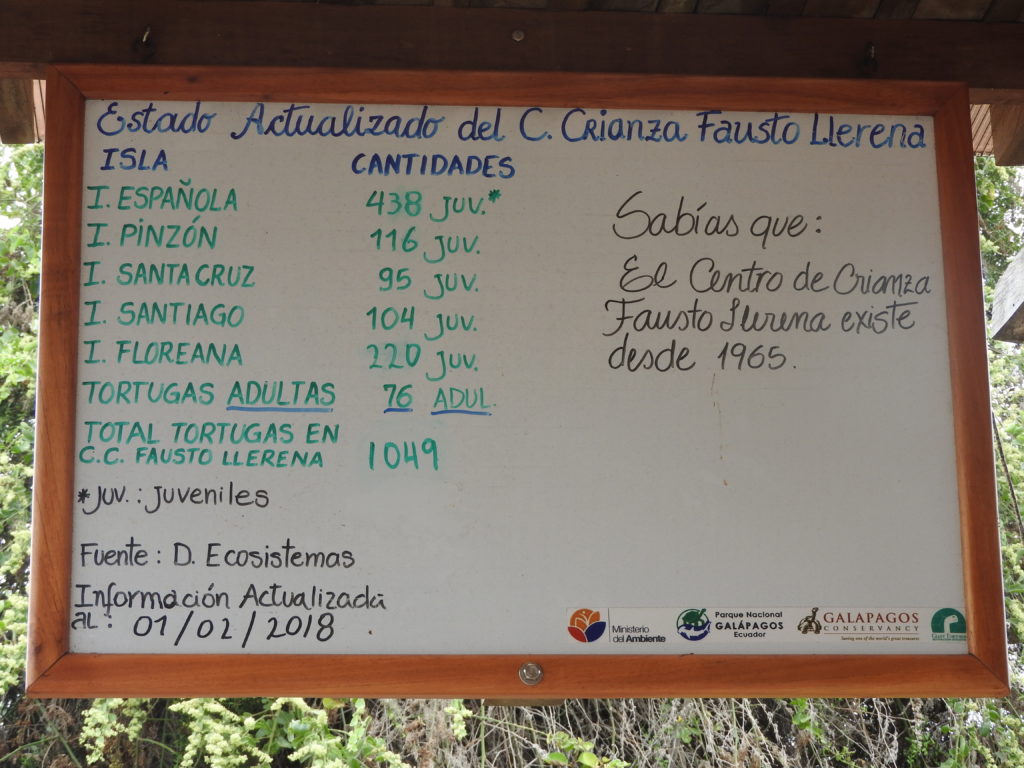

So, about the breeding program…. if the tortoises were left to their own devices, a lot more species would become extinct, because the introduced animals eat the tortoise eggs, and so it’s very hard for new tortoises to reach adulthood. So what they do, is collect the eggs, incubate them in the breeding centre, and then once the tortoises are around five years old, and much less vulnerable to predators, they release them into the wild.

This program has been really successful – it has brought several species back from the brink of extinction (eg. from less than 12 tortoises left on Española to around 1000 nowadays). The breeding centre explains this process, and you can see the different tortoise species from the different islands.

The main difference between the species, is the shape of their shell. The ‘saddleback shape’ means that the tortoise can raise its neck high up. This shape is found on tortoises from low-lying islands with no highlands. These islands are very dry and have very little vegetation. With this shell shape, the tortoise can stretch its neck up and eat bits of cactus which are high off the ground. The other shape – ‘domed’ – is found on tortoises from islands with a wet highlands area. There is plenty of grass and other vegetation to eat on the ground – so they don’t need a space in their shell to extend their necks.

It was fascinating learning about the tortoises, and having a look at some of the different shell shapes, and we spent most of the morning at the centre.

There was one more place to visit as part of the breeding centre, and it was a very sad place. It was a place where we learnt the sad story of ‘Lonesome George‘ .Lonesome George was a tortoise found on the island of Pinta in 1971. He was the only tortoise left that they could find on the island – all the rest had been wiped out in the 1880s by sailors and whalers taking them for food.

He was taken to the breeding centre, with the hope that one day another of his species would be found for him to mate with. No other member of his species could be found anywhere, and so George became the last of his species, and lived the rest of his life at the breeding centre.

Some female tortoises of closely related tortoise species from other islands were put with George for him to mate with. George mated twice, but all the resulting eggs were inviable – meaning that they could not hatch.

George remained the last surviving Pinta island tortoise for his whole life. The ranger at the centre said that he didn’t seem to want to mix with other tortoises in the breeding centre in the usual way – probably because he had grown up all alone on Pinta without ever seeing another tortoise until the age of 60 years old – when he was brought to the breeding centre.

George died in 2012 at the age of around 100 years old – the last of his kind. His body was preserved by taxidermists, and you can now see him perfectly preserved inside a glass exhibition case in a special room at the centre. You can only access this room with a guide, and it’s a bit surreal to enter this dark room and stare at the stuffed body of Lonesome George while the guide tells his story.

We felt a bit sad after hearing about Lonesome George, but cheered up a bit when we saw the Galapagos land iguanas. These are also part of a breeding program, as they are unique to the Galapagos. In fact, the Galapagos has three unique species of land iguanas – this one, and also the pink land iguana, and the Santa Fe land iguana.

Incredibly, all these land iguanas, and also the marine iguanas, are descended from some ‘normal’ iguanas that arrived in the Galapagos somehow 8 million years ago – and then evolved into three species of land iguana and one species of marine iguana – the only swimming iguana in the world! (We LOVE the marine iguanas…:-) ) Those of you paying VERY close attention will have remembered that the oldest islands are only three or so million years old – so how did the iguanas get there 8 million years ago???? It is thought that they arrived on islands that existed 8 million years ago, but are now submerged under water.

The island of Baltra – where the airport is located – lost of all its land iguanas – so it is being re-populated with them via a breeding program. These iguanas look really cool, and are a lovely sandy colour – quite different from the green iguanas of Guayaquil located 1000km away on the mainland. We hoped that we would have a chance to see one in the wild on one of our day trips.

As well as the breeding centre and exhibition area, there are two beaches that you can visit in the area – Playa Ratonera, and Playa de la Estación.

Playa de la Estación was not that exciting, but Playa Ratonera was awesome! 🙂 There were small trails all along the back of it, it was practically deserted, there were good views out to sea, and there were TONS of lovely marine iguanas! 🙂 We spent AGES there just walking around and looking at marine iguanas… all of the following pictures were taken at Playa Ratonera…

We liked it so much on this beach, that we vowed to return the next time we were in Santa Cruz… 🙂